In the previous edition of “What’s a Dual-Sport motorcycle?” I outlined some ground rules and essentially drew a circle around the bikes I feel fit squarely in the segment. While talking to motorcyclists that are considering the purchase of a new dual-sport, I find that many are still unfamiliar with the breadth of models available, moreover the divide in both cost and capability between the bikes at both extremes of the range.

With that in mind, I want to describe the various sub-categories of dual-sport motorcycles in more detail. I also want to highlight some of the models available from rarer brands. If you have the patience, I’m gonna take a deep dive into the specifications of various models. Lastly, I think there’s a demand for a motorcycle squarely in the middle of the segment that I don’t think currently exists from any of the manufacturers.

What Dual-Sports are currently for sale

I full-well understand you can get on the internet and find a deal on a gently used Suzuki DR350. Considering that many older dual-sport motorcycles were built from cast iron, there’s an infinite list of reliable “street and trail” motorcycles available on the used market. In the interest of discussing current trends in the market, combined with a little pandering to folks that prefer to buy new or “barely used”, I am going to focus on models that are currently in showrooms or bikes that were for sale from the factory in the last couple years.

Considering that criteria, I’ve created a list of 24 motorcycles that fit my definition of “Dual-Sport”. I have decided to omit the new Husqvarnas in this case because they are incredibly close to the offerings from KTM. For folks that are very active in that sub-category, I can appreciate there are nuance differences between a KTM 690 and the Husky 701, but on the stat sheet, they are arguably identical and likely chasing the same customer.

Recent Model Year Dual-Sports:

- 2022 KTM 350 EXC-f

- 2022 KTM 500 EXC-f

- 2021 KTM 690 Enduro R

- 2020 Yamaha WR250R

- 2020 Yamaha XT250

- 2020 Suzuki DR-200S

- 2022 Suzuki DR-Z400S

- 2022 Suzuki DR650

- 2021 Kawasaki KLX230

- 2021 Kawasaki KLX300

- 2021 Kawasaki KLR650

- 2021 Honda CRF300L

- 2021 Honda CRF300L Rally

- 2021 Honda CRF450RL

- 2021 Honda XR650L

- 2021 Beta 500 RR-S

- 2021 Beta 430 RR-S

- 2021 Beta 390 RR-S

- 2021 Beta 350 RR-S

- 2021 SWM RS 500 R

- 2021 SWM RS 300 R

- 2021 SWM Super Dual 600

- 2021 Zero FX ZF3.6

- 2021 AJP PR7

Old School Dual Sports

While I’m not going to pretend I’m a motorcycle historian, I feel safe making the accusation that the XR650L, DR650, DR200, and XT250 are the ancestors of many of the motorcycles on this list. Successor to the XR600 (kind of), the XR650L was released in the early 90’s and is virtually unchanged today. Like the other bikes in the sub-segment, the XR represents a reliable, Japanese, air-cooled powerplant, with long-travel suspension, reasonable maintenance intervals (for the era), and simplicity. I have a strong suspicion that these models are short for this world. However, if you’re not concerned about fuel injection, upside-down suspension, liquid cooling, and performance, this subgroup gives you a lot of bike for not a lot of money. Moreover, aside from its weight, the XR650L still scores very high in this category as far as capability, assuming you’re prepared to wrestle the 350-ish pounds; but more about that later.

Race bikes with plates

I mentioned this group of bikes repetitively in the previous article. In recent years I’ve seen more street-legal off-road models being offered, namely Honda’s CRF450L. Beta offers all four of their 4-stroke off-road race bikes in street-legal trim levels. KTM has cut their 250cc offering in recent years, but their 350 and 500 enduro models are offered in “EXC-f” DOT compliant variants here in the US. SWM also makes two street-legal off-road motorcycles, but I’ll get into that brand a little more in a minute.

Most of the models in this group are European, and all of the big-brand models have an off-road only equivalent elsewhere in their lineup. It goes without saying, these bikes are intended for primarily off-road use, having road-going accouterments so you can legally use public roads to connect trails. It’s not to say that bikes like the KTM 500 are incapable of being a “go anywhere” dual-sport. The point is that these bikes emphasize performance at the cost of maintenance. These are unquestionably the most capable motorcycles in the segment, but that capability comes at a price.

Low Maintenance Machines

The most modern of the Japanese subset of dual-sports represents the antithesis to “Race bikes with plates”. Many of these bikes are the evolution of “trail bikes” that have road-legal equipment. Long-time readers know my experience with the CRF250L. Needless to say, that bike brought me to this segment and even following its sale, I still find myself most at home in this sub-set of bikes at this stage in life. Bikes like the 250L have given way to the new CRF300L (and Rally) but trace their roots back to the CRF230L, which hearken back to the XR models of yesteryear. Kawasaki offers the new KLX300, successor to the KLX250, but also the new KLX230 which is a road-legal version of their trail bike. Arguably encroaching on the adventure segment, the KLR 650 returned from a short hiatus in 2021 with some modernization, mainly fuel injection. With a 6-gallon gas tank and almost 8,000 miles between oil changes, the KLR is the touring king of the dual-sport segment. An orange antagonist to the KLR, the KTM 690 Enduro R brings buckets of performance to this segment at the price of about 350 pounds. The 690 stands atop this list with the most horsepower, has respectable suspension, and only needs fresh oil every 6,000 miles. The 690 also commands the highest asking price, just barely edging out the KTM 5-hundo.

Rare Birds

After patrolling the internet and asking Instagram what everyone’s favorite dual-sport is, I discovered a few “fringe” brands or unexpected entries to the segment.

Speedy Working Motorcycles (the before mentioned SWM) is an Italian motorcycle manufacturer that inherited the intellectual property from Husqvarna when the brand was purchased by KTM. Today KTM builds bikes with white plastics labeled Husqvarna with the same powerplants and major components, leaving the legacy engine designs to the owners of the before mentioned intellectual property. While I don’t know a whole lot about the pre-2014 era motorcycles, I’m under the impression that the bikes offered today by SWM are very similar. Moreover, at least on paper, these bikes are very capable. SWM offers a 300 and 500 enduro model, both street legal, along with a 600cc model that competes with the DR650 and KTM 690 in stats and intended consumer.

Considering what I just said about SWM, AJP is a Portuguese company that specializes in custom motorcycles. AJP has several bikes in the Enduro and supermoto segments along with the street-legal PR7. The PR7 is somewhat analogous to the KTM 690 and the KLR; performance-oriented like the 690 with premium suspension, but also has a full rally fairing for folks that are more interested in long-distance dual-sporting. Like SWM, the PR7 is powered by the pre-2014 Husqvarna TE630 engine, but with a frame bespoke to AJP. An argument could be made that the PR7 is a factory-made rally bike aimed at mortal motorcyclists like myself. Alternatively, the PR7 is perhaps the most advanced adventure motorcycle on the market; weighing 365 pounds, with 10 inches of suspension travel, carrying 4.5 gallons of gas, the PR7 barely edges out of the T7 at $11,500. Not a bad deal to change oil every 3,000 miles.

While better known for their electric street bikes, Zero also offers a dual-sport model in a few different trims. With no engine to service, electric motorcycles prove to be an interesting answer to the dual-sport question. Assuming the electrics prove to be hardy enough, and range isn’t a deal-breaker, the Zero FX has comparable suspension travel to the older 250-ish models, with none of the mechanical fussing. Also, among race bikes, a $9500 price tag isn’t shabby considering you’ll never change oil or check valves; after a chain conversion, you can just buy tires and ride.

The nerdiest of all stat sheet racing

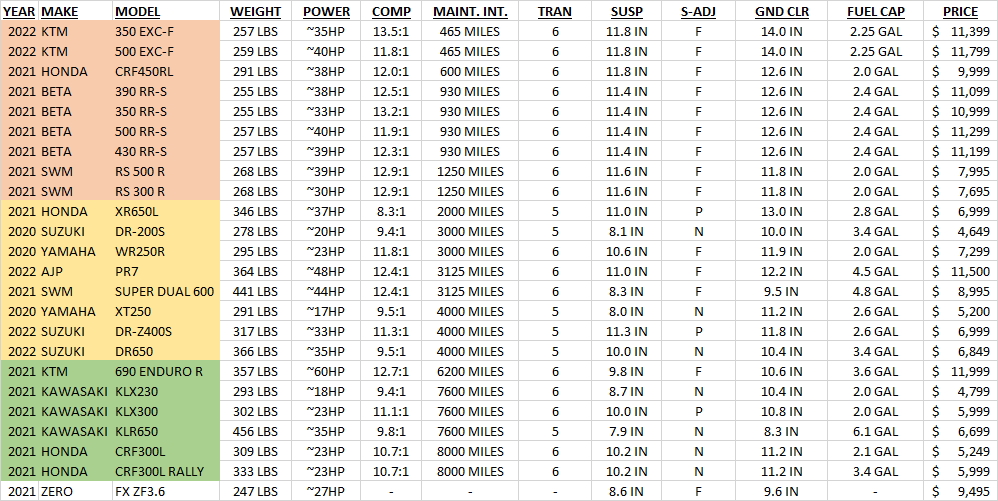

When folks started naming their favorite dual-sport motorcycles I started a list. Being a nerdy engineer I put that list into excel so I could sort by brand. Naturally, I couldn’t help myself, so I started populating weights and prices. This led to including performance statistics from the manufacturer’s website. Being a stickler for maintenance, I looked up the oil change intervals in all of the owner’s manuals. When you can see the entire segment and compare each model against the other by simply sorting based on specification, it’s interesting to see how each of them stack up. Again, my fascination with the numbers got the better of me as I decided there must be some kind of “rating system” I could apply to each machine. I scored each specification in order from 1-24 in Olympic format (equal scores make a tie, i.e. all 4 Beta models have identical suspension travel).

The categories were weight, rear-wheel horsepower, engine compression, maintenance interval, transmission (5-speed vs 6-speed), price, suspension travel, suspension adjustability, ground clearance, and fuel capacity. When added together, ultimately the motorcycles with the lowest score made for the “highest performance” bikes considering the averages. This became more interesting when the scores are adjusted for price.

When sorting strictly on performance, the KTM and Beta 500s reign supreme with premium suspension, thoroughbred engines, and big horsepower. Interestingly enough, the old XR650L comes in 4th despite being 30 years old. That low compression, long-travel suspension, and 650cc lump still does well despite the weight. When adjusted for cost the Big Red Pig moves to the top considering you get nearly equivalent performance (on paper), but at nearly half the cost ($6,999). This becomes more interesting when you see the Honda CRF300L Rally move up to 3rd place with its 8,000-mile oil change interval and 3-and-a-half gallon gas tank. Even more surprising to me was that with no transmission, engine braking, or engine maintenance, the Zero FX lands in 4th place. I knew after comparing stat sheets against the CRF250L that Zero’s “dual-sport” was very close in capability to my former 250cc Japanese multi-tool, but the latest model boasts respectable weight savings and reasonable suspension considering its clear street bias. While range is most certainly a concern with riders likely to find themselves well away from civilization, for urban dual-sport riders, the Zero FX seems like an easy motorcycle to live with, at least on paper.

My scoring system is of course not without flaws. Weight and suspension travel seem like clear delineations when stat-sheet racing, but engine compression is subjective. As far as race bikes are concerned, power, weight, and suspension are key, but in the dual-sport range, I feel the metric shifts more toward reliability, ease of ownership, and flexibility between on-road and off-road performance. I chose engine compression as a quantitative statistic to represent engine stress, reliability, along with “tendency to flameout”. For folks unfamiliar, the 4-stroke thoroughbreds like the KTM 350 and CRF450L require a great deal of clutch work to avoid “stalling” at low speeds. Many have suggested an aftermarket ECU is absolutely critical for dual-sport riding on the CRF450L. Based on my own experience, I don’t want one because the flameout issue is so prevalent despite modifications (EveRide and I agree). Fuel capacity also doesn’t equate to overall range, which I think is more important. Unfortunately, those numbers are more ambiguous in this category considering usage varies so widely, thus forcing me to use capacity as an empirical measurement.

Ultimately, these are the categories I chose as they’re most applicable to me. Things like “seat height” would also be relevant, as would subjective categories such as “comfort”, “wind protection”, and “highway vibrations”. I welcome criticism and most certainly conversation on these stats and other ways to slice the segment. Ultimately this spreadsheet proved to be more thought-provoking than I ever could have imagined. The thought of building a race-capable ADV bike out of a CRF300L was born from this exercise; as was locating an AJP dealer.

There’s a bike missing from this line-up

Back in August, I handed off my 250L to a new owner. While I never fell in love with that bike like Rosie the Scrambler, I was no doubt in love with what that bike was capable of. Unfortunately, that motorcycle needed another inch of suspension travel and ground clearance, probably another 5-ish horsepower, and at least 20 pounds of weight reductive measures.

After compiling all of the statistics for the 24 bikes on this list, I couldn’t resist looking at the averages for each of the performance stats. Even with 4 Beta motorcycles weighing down the “race bike” end of the scales, I was still surprised by the results. 307 Pounds, 33 HP, 11.4 to 1 compression ratio, oil change intervals every 3500 miles, 6-speed transmission, 10.3 inches of suspension travel, 2.8-gallon gas tank, for the “low price” of $8,000.

I would argue, “average” does not define “the middle” of the dual-sport category. Considering the CRF300L Rally does so well when adjusted for price, and the CRF300L not too far behind, I started writing down the stats for my “dual-sport unicorn” if I could have one. Starting with weight, if the new 300L is 309 pounds, the KTM 500 weighs 259, and the CRF450L is 291 pounds, is it possible to put a street-focused engine in a new frame to achieve a 291-pound road-ready weight? 291 pounds is a hefty race bike, but an ultra-light multi-tool by comparison. While I love the 35 horsepower of my KTM 350, there’s no doubt I don’t come close to using all of it. After years on the CRF250L, I think 27 ponies is totally reasonable. Considering I want to get back to using regular unleaded, 10.7:1 compression ratio is ideal. As I said, 10-inches of suspension travel is a must, along with a 6-speed transmission, and since the 250L would easily do 90 miles on a tank, 2.4 gallons of gas will get the job done fine. Lastly, while I loved not having to change oil every 8,000 miles, it was $25 and I did it multiple times a season, so reducing that frequency to 3,000 miles for oil and 6,000 miles to check valves is very reasonable in the shadow of the Euro-machines.

When I plugged the unicorn into the stat sheet and tallied up the scores, with a $7,600 price tag, this unicorn bike rose to second from the top of the list for “best bike per dollar”. Naturally, I don’t speak for everyone, but among 50-50 dual-sport riders, I feel many complain about the weight of the Japanese models, grouse about their lack of power, but are more than happy with how much abuse they can handle and still get back in the ring.

Obviously, there’s a massive difference between a bike on paper and riding a motorcycle. All the stat sheet racing in the world doesn’t make for a signature on a sales contract. That aside, this mythical dual-sport creature I’ve described is my “wish-list” for what I want from my next do-all machine. Considering the “average” stats, anecdotal comments, and “internet wisdom”, I suspect I’m not alone. It would be incredible to see Yamaha drop a WR350R on the market in the near future and check all of these boxes for us.

“Nerdy engineer”? There’s no such thing as a “nerd” who races moto and seeks out muddy climbs, slippery creek beds and downed logs to hop. You, Sir, are an Alpha Beta more than you are a TriLamb.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I’m trying to build a bridge between philosophy and science… we’ll see who’s still following when I finish it 🤣

LikeLiked by 1 person